Deposing a witness with limited English

When my brother was a teenager, he was involved in a car accident. He was stopped at a traffic light when his car was rear-ended. My brother was called for a pre-trial deposition. From the transcript:

When my brother was a teenager, he was involved in a car accident. He was stopped at a traffic light when his car was rear-ended. My brother was called for a pre-trial deposition. From the transcript:

ATTORNEY: Were you in school at the time of the accident?

WITNESS: No, I was in the car.

We all know what the attorney was getting at. He was trying to establish that the witness was a full-time student at the time the accident took place. The internet is filled with real-life examples of simple questions gone wrong in depositions.

My brother is a native English speaker, born in the USA to an English speaking family. And he wasn’t being a smart-aleck. He answered the question that was asked. It’s hard enough forming questions for English-speaking witnesses. How much more difficult is it to form questions and examine a witness who doesn’t have a native-level command of English?

If you know you’ll need to depose a witness who doesn’t speak English (or has a weak grasp of the language), you can engage a professional translator. If the witness has acceptable English skills, it may be more efficient to proceed on your own. How do you decide? If it’s your witness, speak to them first and see how well the witness does under questioning. When in doubt, a reliable, recommended, professional translator may be worth the expense.

How to phrase questions

As we see in the example of my brother, phrasing questions is the key to successfully deposing a witness with limited English.

Be direct – Don’t speak in the passive voice and be as concise as possible. It can be confusing to add unnecessary words that might require translation. For example, instead of:

ATTORNEY: At the time the automobile was proceeding through the intersection, what did you observe the color of the light to be?

Try:

ATTORNEY: What color was the light when the car went through the intersection?

See the difference? Just come right out and ask the question. There’s no need to be superfluous. In fact, it can be hazardous to your line of questioning. “At the time” can have different meanings in different languages. “When” is easily translated and understood in most languages. Also “proceeding through” has a specific meaning in English that lawyers understand. In contrast, the same phrase may be difficult for a translator to convey. “Went” is a simple and direct past-tense verb that is more easily understood.

Don’t use expressions, colloquialisms, or slang

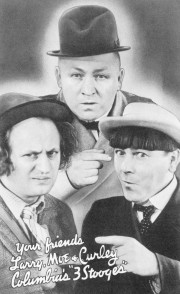

There’s an old expression used by Yiddish speakers who immigrated to America – “Don’t hock me a chinik!” It’s understood to mean, “Stop bothering me!” and is based on the irritating noise of someone banging on a teakettle or the lid of the teakettle banging against the pot as the water boils. Literally, it means “Don’t knock a teakettle at me!” The phrase became known and used by Americans without contact with Yiddish speakers by appearing in The Three Stooges short films.

In an attempt to relax the witness, or keep questions simple, we fall into the trap of using common English expressions. When talking about an accident, an attorney might say, “That must have scared you out of your pants!” The translator may literally translate your statement and confuse the witness. “No, my pants were still on. Why are you asking about my pants?” You’ve just lost your momentum, your train of thought, and perhaps made the witness feel silly. Phrases like “easy as pie,” “shouting at the top of your lungs,” or “freaked out” aren’t easily translatable and can be the source of confusion. Don’t underestimate your propensity to lace these linguistic gems into your everyday language. While they convey very specific and situation-appropriate information, they may carry a completely foreign meaning to those with limited English.

Local expressions may be the worst when it comes to confusing the witness. “That dog won’t hunt” makes sense in Georgia, but in New York City, people will look at you funny if you utter it in court. Your witness may have a limited command of English, but it will likely be from his locality. Don’t take a chance confusing him with a local expression. Since many every day sayings are generational and geographical, it’s better to stick with the concise language that is easy to understand regardless of where the speaker learned English.

Culture and history matter

An agent from the state elections board visited the home of an elderly couple. The agent was trying to verify the couple’s voter registration form. When the agent asked if the couple knew about the form, wanted to vote, or were citizens, they answered in the negative. Charges were filed against the couple for voter fraud. At the hearing, it was determined that the couple did fill out the form, did intend to vote, and were citizens. Why the confusion?

The couple was from the former Soviet Union. In the Soviet Union, when a government agent shows up at your door, it means something very bad will happen to you. Quite frankly, they were terrified. So they clammed up and denied everything.

Remember that your witness may come from very different society where the political and cultural norms could be at odds with American culture and history. They may not have experience with a fair and honest judicial system. They may be afraid to tell the truth for fear of prosecution or persecution. Don’t try to trap, startle, or confuse your witness. They may see this as a trick to cause harm, negatively affecting your case.

Put thought into your deposition preparation and questions. Make a plan to simplify your language as needed and consider your vocabulary and syntax as you prepare. You can also think of different ways to ask the same question – when in doubt, go with the most concise and direct option. If you present yourself in a professional and courteous manner and thoughtfully prepare your question and language choices, your deposition will be productive despite the language barrier.

Leave a Reply